Blog

- Details

Here in Northeast Switzerland, the November days were incredibly beautiful. I never experienced so much blue sky and clean, clear air at this time of year in all my time in the Danube Valley of Germany. This Californian enjoyed the abundance of light and color in November immensely.

What was hard to enjoy last month was the news. Politics dominated the focus of many people I know here and in the United States. We read, we look, but we are not convinced. We have less and less trust in what we are told through journalistic channels. We are tired of hoping for something uplifting to happen in the world and being disappointed. We then prefer to surround ourselves with voices and videos from those we still like and want to let into our overfed brains. We know there are terrible wars going on using weapons made by our own countries. We know there are many social injustices and not less of them. We hear threatening slogans from ascending political parties, and it might seem to us that it is all too painful. We need to be soothed.

But I feel most of us realize there is a connection we cannot ignore to suffering in faraway places. We can find many explanations for the problems of the world. But one can certainly say that the European and Euro-American colonial mindset has had many harmful effects over the centuries. Traces of colonial thinking like racism and entitlement remain in many people’s language and in many people’s attitudes, even if we think we know better.

Such strong currents in our history are difficult to confront and can make us feel helpless to enact positive change. We would like to overcome hate and violence and do something to help the world find peace and equanimity. I have been trying to find my way with this challenge for a long time.

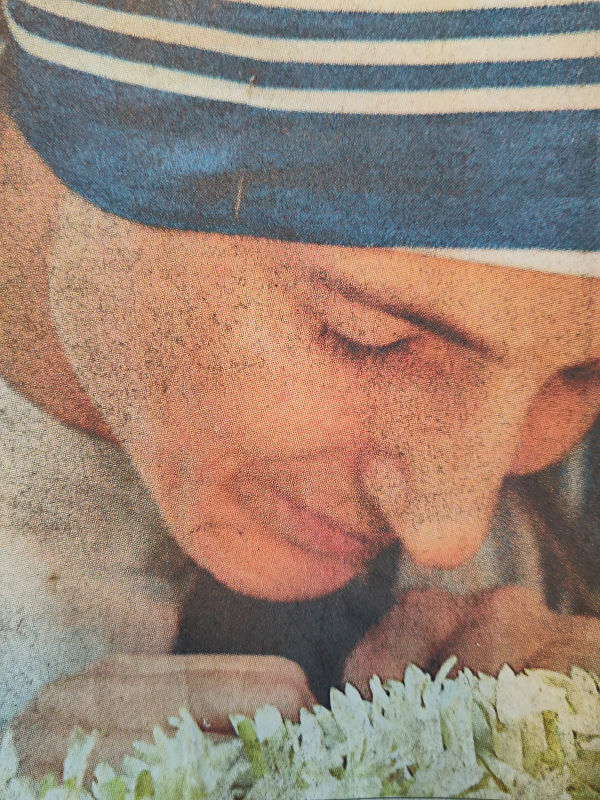

I have visited India many times over the last twenty years. I have had many interesting experiences there, but one I find it important to share in light of this theme is my time working with Mother Teresa’s nuns, monks, and volunteers in Kolkata. Those three months remains very special in my memory, for it is here that I found work that went straight to the heart of this matter.

I have visited India many times over the last twenty years. I have had many interesting experiences there, but one I find it important to share in light of this theme is my time working with Mother Teresa’s nuns, monks, and volunteers in Kolkata. Those three months remains very special in my memory, for it is here that I found work that went straight to the heart of this matter.

I arrived in West Bengal with the intention of doing work at Kalighat, the original hospice Mother Teresa established after doing all her work on-site in the slums. Mother Teresa had died five years before my arrival in Kolkata. But the nuns and monks often spoke of her, and with great respect. She was not perfect. She argued with her nuns and had many disagreements. But she could always apologize, they said. And she could always forgive other people’s mistakes.

Mother Teresa was also an amazing worker. I was told and shown what kind of work she would do, and how long she would do it. Her capacity for ‘doing the dirty work’ surpassed anything her later followers were capable of, or so I was told.

I spent my first days in Kalighat cleaning in the kitchen. But soon I was out on the floor with the ‘clients’, who were all very thin, very sick, and very poor. I spent many hours feeding them, carrying them, bathing them, and even cleaning them. If someone died, I would help clean the body and wrap it in a white bag.

I would often accompany Sister Delphine, the lone woman working on the men’s side of the hospital. I sometimes had to hold the men while wounds were tended to, wounds and sicknesses I could never have imagined. But somehow, this gruesome work was enjoyable and fulfilling.

I never saw a blue sky while walking the streets of Kolkata. So much poverty, so much pollution. But the eyes of the people I met were not dreary. They often shined. I felt their hearts were alive, and I felt that looking at those less fortunate materially and offering them a friendly and respectful gesture that was not condescending turned out to an offering that even beggars took as nourishment. Their gazes and smiles were also a kind of energetic gift that supplied me with energy.

I had good fortune with the Missionaries of Charity, the male order of monks. I came to live with them, pray with them, work with them, eat with them, play chess with them, and even meditate with them. They treated me with a great deal of kindness. When we were out in the city one day, one monk saw that we were approaching a very busy street and took my hand. It was not easy initially for me to accept this gesture of caring for a whole kilometer! But I did settle into it and could enjoy it. This was brotherhood.

I found it a privilege to work at Kalighat, doing some of the most difficult tasks I would ever face. I could finally experience an appropriately vital expression of the practice I had learned for many years practicing Zen Buddhism in Japan And I came to understand a couple things Mother Teresa said that became more true after my experience there.

One thing she put very well is: “Love until it hurts.” I certainly met my limits of how much I could tend to the people in Kalighat. My body and mind needed time to process the quantity and severity of disease. But I was also able to observe other monks, nuns, and volunteers. I gained courage and endurance. The work was very intimate. Compassion could not be conceptual. Either I could do things or I couldn’t.

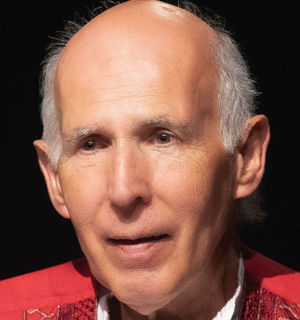

Something of the encounter with a Zen Master here. Harada Roshi was very severe with me at times, but his intention was that I would not waver in my desire to be of service to individuals and to the greater good, even when the circumstances were very strenuous. To have this ‘extra’ energy beyond being nice or kind, to be able to see what needs to be done to relieve suffering and to have the right stuff to do it, this was what Harada Roshi lived and what was my great inspiration for fifteen years of monk life.

In our modern society sharply focused on optimizing itself, I ask where what I understand as the power of love fits in. Long-term partnerships, family and working relationships, and friendships demand incredible patience and courage if they are to grow and flourish, and such virtues seem ever more difficult to access if I am thinking all the time about my work-life balance. I need to know my limits, but have I stretched to my limit?

Another important remark Mother Teresa said after returning from a visit to North America: “The people in India are very poor. But where I was, the people are much poorer.” Intuitively, I knew what she meant. I am a Euro-American, and looking at the amount of hate, violence, and loneliness that voices itself daily, I can say that there is some serious spiritual poverty where I come from. If we can enrich ourselves again in understanding what it is to be expansive and wealthy within and experience how that changes the world around us, we become more confident that the complex difficulties we face in the outer world can be overcome, and that others can do it as well.

Another important remark Mother Teresa said after returning from a visit to North America: “The people in India are very poor. But where I was, the people are much poorer.” Intuitively, I knew what she meant. I am a Euro-American, and looking at the amount of hate, violence, and loneliness that voices itself daily, I can say that there is some serious spiritual poverty where I come from. If we can enrich ourselves again in understanding what it is to be expansive and wealthy within and experience how that changes the world around us, we become more confident that the complex difficulties we face in the outer world can be overcome, and that others can do it as well.

India has major problems. Violence is there, pollution is there, hate is there too. But I found people who shared something about love there that I either hadn’t encountered or hadn’t recognized at home. In some way, those experiences enrich my life today in a very Western World.

In thinking beyond wanting to be better than someone else, beyond blaming someone else for our problems, and beyond work-life balance, there is a pure and powerful urge within human beings to care for the earth and the beings on it. To live that infuses our life with meaning. And, it hurts sometimes.

- Details

Autumn has come to the Northeast of Switzerland. The colors are delightful, the air is clear and crisp, and the Säntis Mountain is capped with snow again. I truly love my first season of autumn here.

Just last week, I was basking in a much warmer place, on the coast of Portugal. The vastness of the ocean, the smell of salt water and feeling it on my skin, the intense motion of wind, waves, and clouds, the vivid sunsets, and the stars at night penetrated my being. I moved slower and felt deeply connected to all the natural elements. My early October was a potent period of vitalization.

I also took my first surfing lesson. My wife surfed for many years and she wanted to get back into it. Yes, I grew up in Southern California near the beach, so one could assume surfing for me would be like playing soccer for Germans. But, I loved other sports and had never attempted to ride a wave with a board. Friends in Corona del Mar high school would surf before school and sleep during most of their classes during the day. I remember well, seeing their happy exhaustion, their heads resting on their desks, even snoring in class. The teachers couldn’t do much about it!

If I would wake up early in the morning, I would study. I wanted to go to university. My friends wanted to enjoy their lives fully where they were. I felt they were courageous. I envied them, even their snoring.

After my first few hours in the waters off the Alentejo coastline, I was extremely tired and sore. I took a second lesson a few days later and was much more relaxed. I also had less soreness afterwards. I think it was because I learned a couple things, and those things apply to life in general, so I want to write about them.

In my last blog, I wrote about lingering in neutral. There certainly seemed to be no time to remain passive when trying to catch a wave that first day. I tried to do everything right.

Paddle

Push – up when you have the wave

Raise and stabilize back leg

Get up, bend your legs and don’t look down!

Well, I never made it out of the white-water, but the Atlantic offers good push in the white-water, so I did have some rides. And what I had to learn that was really important and not easy: to look up when I paddled, to look towards the beach in the direction I was going throughout the entire process. But most importantly, to wait, to feel the wave taking me before acting. Indeed, a paddling-lingering in neutral was required!

On that first day, it was far too easy to worry about my technique, about the weak right knee, about the placement of the foot, about my lack of practicing enough push-ups the last months, all of which made it impossible to get a decent ride. I kept orienting downwards towards my weaknesses and looking down. And, I fell, and fell, and fell. The board flew, and flew, and flew. I had some fun, but it was very strenuous. My tanned, longhaired surfing teacher Diogo just kept saying, “Don’t look down. It will be easier.”

The second experience two days later was much different. I tried not to worry so much about what my body was doing and focused on ‘feeling down’, feeling for the wave to take me while looking forward. I gazed and trusted that my body below would follow. And, good stuff happened rather easily, I was up and was able to catch a few rides to shore. It was almost too easy. It was as if the Atlantic Ocean took me along for a ride. It guided me. It wanted me to have some fun. My surfing attempts didn’t always work out like poetry in motion, but the experienced moments of stability were clear.

Something important lies in what I experienced in Portugal. I am indeed planning to do some push-ups regularly and surf again soon. But what is more important for me today is to reflect on how this attitude of waiting, relaxing, and trusting, of looking forward with my head up in the present and not down in deliberations of right and wrong, strong and weak, good and bad, past and future, allowed me to feel the support of a bigger force. There was a power present that could take me along and allow me to become upright rather easily. I could glide, smile, and enjoy.

In America, elections are coming. In the Middle East, there is catastrophic war happening with more conflict on the way. Here in Europe, a long drawn-out battle sucks billions of dollars out of people’s pockets and damages millions of lives. As a collective, much of humanity lives in very tense times.

Our individual lives have unavoidable challenges. The body ages, we see friends and family with illnesses. People we care about have difficult situations to work through, needy of support. It is easy to look down, to blame others, or to feel frustrated, overwhelmed, and helpless.

But, yes, we still try to stand up and help the world. We do our best. With all our physical and emotional weaknesses, our habits of distraction, our imperfect personalities, we try to keep looking forward, attention up and forward, and trust. We have the ability to get up, find our flow, and help others get up and find their flow as well. We want people in this world to feel this resilient trust, this gliding, this enjoying of life. Ultimately, we want to have the courage to get out there again and connect to this bigger power that can then carry us (and others) in the direction we are meant to go, no matter how many times we crash and splash.

I think my high school friends would be surprised to know that I went surfing. I still admire them, and hope they are able to surf the challenges of life with the confidence they had on those early mornings many years ago. I hope you can too!

- Details

Wonderful landscapes continue to bring delight to my senses here in Switzerland. Mountains, lakes, forests, rivers, green fields, but also gardens full of tall, bright flowers, traditional farm houses, and small groups of meandering cows catch the eye and please it.

When I contemplate why that is, what it means to see and feel beauty and connection, I often consider whether the lack of violent conflict this country has experienced in the modern era allows the resonance of natural peace in myself and in the Nature around me to be expressed in a stronger way.

Peace – if we don’t know it within ourselves, how should we know how it can manifest among hostile communities and countries in the world? Do we know it with our families, with our co-workers, or with our neighbors? How do we experience it, recognize it ,and share it? I have wanted to understand this for a long time.

Switzerland is known for its government being neutral. According to constitutional law, they will not take up arms in a conflict between two nations at war. The Swiss themselves often mention this, and often they add a few comments to share that they are aware of awkward compromises their governments were responsible for in the past while still calling themselves ‘neutral’. But, I also note a pride concerning the attitude of neutrality that permeates the Swiss mindset. For many Swiss people, perhaps the majority, it is common sense to think that interfering when two are having a problem is not so smart, and that peaceful solutions are possible

Peace. As an American, that is a word that feels outdated, a hippie ideal. But no, I know that millions of Americans are dedicated to this cause. To support it, I suggest that benefits arise from this characteristic of neutrality, such as being able to live together on this planet. I sense it here in Appenzellerland, in the quality of my life, and in the quality of the people I meet here daily. What does it mean to be neutral?

Peace. As an American, that is a word that feels outdated, a hippie ideal. But no, I know that millions of Americans are dedicated to this cause. To support it, I suggest that benefits arise from this characteristic of neutrality, such as being able to live together on this planet. I sense it here in Appenzellerland, in the quality of my life, and in the quality of the people I meet here daily. What does it mean to be neutral?

There is a deeper meaning to neutrality for the individual. It doesn’t mean just not taking sides. It doesn’t mean always being calm with a Buddha-like smile on our faces. It’s not a state of stoic non-feeling. Neutrality is clear-minded awareness that a variety of perspectives exist. When we are not clinging to our private world of inner arguments and justifications, likes and dislikes, friends and enemies, and deeply interested in human beings before opinions fog over our intuitive power, we are capable of naturally entering an energetic state of neutrality, which is not stagnation or mere passivity. We don’t mix things up. Neutrality allows things to stay organic, to grow, to calm down, to heal, and to become powerful.

It is there in a car, that big ‘N’. Almost every car I have driven in Japan and Europe have been stick-shift. Here, we consciously shift into the other gears, but we don’t manage it without tapping into that neutrality for at least a moment. Cars without a stick-shift seem to skip neutral, and almost all cars I drove in the USA are automatic. An article about cars in Google even tells me that ‘Neutral’ is a dangerous gear in automatic cars. You lose control. But I like to linger a bit in Neutral when I drive my stick-shift car here in Europe. It feels good not to be in gear all the time.

Isn’t it about time to give space for ‘neutrality’? Not primarily in the political sense, but in the physical, psychological, and energetic sense. A tree has branches. We identify the tree by its leaves and flowers, and by the shape of its branches. But what is really giving that wonderful tree life? What is the source of beauty here? Light, water, and oxygen enter the tree through the leaves and bark, but the movement and transformation of those elements into energy has to connect to the roots somehow. For this, it goes over the middle, the stem, the trunk, the gut, and the heart. This is the unseen neutral zone, where nothing is easily visible or palpable to our senses, but where actually everything has to move through to get authentic movement and power. We human beings function like this, animals too.

We humans can get in touch with these inner movements. We can observe, support, and enhance them. However, in our history, though we Euro-Americans claim to be individualists, we often give over our observational and intuitive powers to rash actions, explanations, and the advice of the experts. In the complexity of it all, we can lose faith that we are capable of sensing deeply what is going on inside us. Decisions become very difficult. We sit on one branch of our tree and lose a sense of connection to all the others on our individual tree, and then to our collective forest.

The internal dilemma becomes the external dilemma. It happens everywhere. Many of us Americans may be facing a dilemma, a sense of stagnation. We so much want to know, to go, to lead, to get somewhere that is really wonderful. It’s frustrating these days.

In the article I referred to about auto transmission, it says, “Use Neutral when your car is stuck.” I like this sentence. When things are not moving smoothly, to come back to neutral, to inhale, to stop forcing things into one gear or another, to observe things, to loosen up. Where are things moving on their own?

This neutrality is not giving up. We learn trust, and trust is a wonderful thing to feel. It lifts our spirits. We regenerate and are ready to approach great difficulties with courage and creativity. And those virtues are not cultivated by an exhausted or ‘driven’ thinking mind. They arise from connection to our whole being, to our roots as energetic living beings, very much a part of all other living beings. At the core, love lives. And from here, I, an American, want to see the world, from here I want to work with and for others, from here I want to enjoy my life.

I hope to get better at accessing neutrality, not judging, not forcing, not tampering where I don’t need to, and hopefully I can share the resulting vitality and optimism I feel with my family, my beloved Americans, and with the world.

- Details

So much natural beauty around here! As the Japanese saying goes, ‘Where I am is the dojo’; where I am consciously and experiencing whatever I have learned, practiced, understood, and seen. Harada Roshi, my Zen Master, used to make a rolling motion with his hands and repeat in his deep voice, “Washing mind, washing mind.”

I often have to smile these days. I am deeply touched by the magical clarifying powers experienced on each new hike in the local mountains in our corner of Switzerland. It’s nice to live in a beautiful place. I grew up near Disneyland in Southern California, also a place where people seek and perhaps find happiness. I think I went there fifty times or so. But, as a youth and young man, I didn’t find it easy to smile, not at Disneyland, not for a camera, and certainly not in front of a mirror. I had a very serious inner life, filled with doubts about myself, the state of the world, and later, the state of my country. For various reasons, it was more scary than satisfying to think about my future or the future of mankind.

It is a long story of happenstances that brought me now to this this country known for its cows, cheeses, and banks. And for its Nature! Many people have come to Switzerland for refuge, and maybe I have as well. The Nature does inspire clarity of mind. Does clarity lead to happiness?

Some of the people that have revolutionized my life in early years and still inspire me through their clear expression are from this country or have spent years here. They were rare minds and are heroic figures for me. I name some of them:

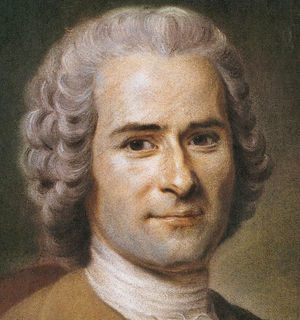

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva and awoke to a deeper connection with Nature on Lake Biel. His Noble Savage inspired me to quit college in 1981 and head to the Matterhorn in the southeast of Switzerland (I found the place much colder than expected and returned to UCLA humbled and intent to learn German.)

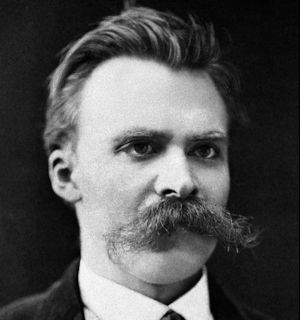

Frederick Nietzsche, who I discovered as a student of History at UCLA , helped me (and many others) to raise the intensity of my thinking ‘beyond good and evil’. He lived out the last chapter of his life in Sils-Maria and was fond of seeking out such energetic hotspots to support his thinking and writing.

Hermann Hesse also left his homeland of Germany for Switzerland and did all he could in his writings from Montagnola near Lake Lugano to convince early 20th Century Germans to be better than mere soldier-pawns. Those men weren’t able to listen, but later generations were more determined after reading him to aspire to a deeper vision of life and reject catering to materialistic and militaristic trends. I listened.

Rudolf Steiner brought revolutionary and practicable insights to the fields of medicine, agriculture, education, and art. His ‘inclusive’ communities were important resources of information for me on my path of social work. He built the mecca/center to his anthroposophic movement in Dornach. His teachings of human history have also expanded my understanding of evolution and progress immensely.

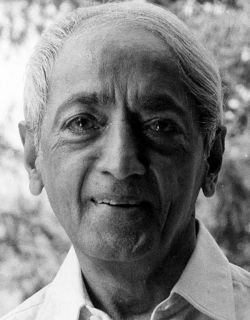

Jiddu Krishnamurti turned my life upside down when I was sixteen with the book ‘You Are the World’, sharing his critical, compassionate, and uncompromising views from his lucid mind. He came to Saanen, Switzerland regularly from 1961 – 1985 to speak, but also to rejuvenate. I was able to attend two talks of Krishnamurti in Ojai, California and the clarity of his presence still touches me. He was the first living evidence I experienced beyond books that silence is alive and that a human being can live a truly deep and beautiful life.

Mario Mantese, Master M is a very special present-day wisdom teacher who left his home in Switzerland as a young man to be a bass player for the pop-funk band Heatwave. After having gained profound insights in a near-death experience, he began to write and offer teachings all around the world. He resides in Western Switzerland. I have the good fortune to attend his gatherings and have translated some of his books with the aspiration to resonate more deeply with his teachings of ‘pure love’. Mario and the work of Master M prove to me daily that one can have a ‘normal’ life in the world while deepening one’s spiritual life. Light and love are our foundation, and we can live from it.

These are some of my mentors. I find them remarkable and they continue to remind me how big and clear the mind can be. They have helped me to ask good questions and to angle my mind/heart in good directions. They reflect to me that one single life can be significant. To experience deep qualities of the human heart and share them is to help humanity move beyond the crudities and cruelties that still hold the collective human condition down in defensive survival modus most of the time.

It feels good to be in Switzerland and see myself smiling honestly. We certainly don’t need to smile all the time, but I hope you are able to feel your mind is clear, that you can smile naturally and share what’s behind it wherever you are. The places and the people who loved and inspired you live through that smile. It’s beautiful!

- Details

My wife and I recently took a magnificent walk in the mountains. The feeling of content known to many after climbing a steep path and arriving at a clear lake was mine as well on this day. The grandeur and majestic stillness of the powerful Alpstein massifs elevated my spirit. I felt easily connected to my breath and to the earth. At the same time, I felt a fondness for all the living beings on it, especially the mountain toads who continually popped their eyes above the surface of the water as if hoping for a conversation.

I drank a bowl of matcha with my wife that day at the shore of the Fählensee (a lake up among the peaks of Appenzell where we live) which enhanced my heart and senses with even more fresh energy. A power within sunk down with the green tea into the water of the lake. My eyes seemed to expand beyond the margins of my physical body, absorbing the powerful emanations from the snow-capped peaks lined by the feathery clouds in the April sky. What a fantastic space to and inhale and absorb this magnificent existence!

I mentioned in my first writing of this blog that helping others was important to me. I also ask myself, what really helps? How do we really help others? I can enjoy this moment by the lake very much, but when I leave, can I really help anyone in this complex world?

I found myself a ‘helper’ very young, as an attendant to my older brother Michael, who was afflicted with Duschenne muscular dystrophy. Pushing his wheelchair, massaging his legs, and carrying his weakened body to a toilet or to a bed were jobs that became very natural to me by the age of 12. In this intimate realm of brotherhood, I felt very useful and connected to someone I loved.

It wasn’t always fun to be the helper. As children and teenagers, my brother and I were constantly arguing. But I never wanted him to suffer. While carrying him, I may have unintentionally banged his foot on a doorway or twisted his ankle a bit hard to get a shoe off. But we both preserved the realm of trust. My hold was gentle but very firm, and Michael never complained about my work. He often thanked me.

When I first heard of Michael’s diagnosis, I wanted to save him. His disease was fatal. He would die between 14 – 20 years-old. I thought I could do something to change or improve the situation. I think this is the root of my search, my desire to help human beings transcend the grim prospects of illness and death.

It is easy now to for me to see how Buddhism appeared in my life. I also see what a tremendous support the teachings and practices have been. The Buddha saw the human condition as suffering unless this transcendence of attachment to the body and its end was consciously experienced. That is the path of the Bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism, one who longs to improve the human condition through awareness and realization, and wants to share it. There is more to existence than life and death, and this awareness can transform our being from being completely self-centered, to living more and more in a heart-connection to all that lives.

When I reflect on those moments of intimacy and mutual support during my childhood as Michael’s assistant, I see that they were short, quiet meditations, focused rhythmic dances that imbued both of us with a larger confidence in the significance of life. We loved and we trusted. That is how I felt at the lake with my wife and the frogs.

It wasn’t easy to find that sense of connection to myself or another person since those years with my brother. And yet, something has shifted over time and good things have happened. The longing for transcendence is no longer something I expect to satisfy through reading a book or attending a workshop, by traveling to another country, or by meeting another person. Transcendence arises from within, pacifying the brain’s tendency to worry, solve, fix, and compensate. I experience anger, tears, and pain, but a light continues to connect me to those I miss, those I have lost.

Michael left this world in 1985. He was an extremely intelligent and generous person, but he was not able to avoid the viciousness of his disease, dying at the age of 24. During his life, I think there was healing. I sense Michael’s presence now as a ray of light that shines through my own person. I would like to write more about Michael soon.

My family story probably caused me to have a ‘helper-syndrome’. But with some real help from others who know transcendence very profoundly, I can embrace the ‘helper’ – path that brought me to this moment in these glorious mountains by the lake with my lovely wife and the curious frogs. It is a moment like those trusting, intimate moments I knew from childhood with my brother Michael. The chance to share such moments is very satisfying.